Introduction

apologia, n. – a defense or justification of one’s beliefs, attitudes, or actions. – Webster’s College Dictionary

I’m getting a bit tired of reading (what I consider to be) increasingly reflexive, dismissive, and (frankly) lazy objections or dismissals of what is broadly now termed generative AI–often abbreviated to just AI (a travesty) or LLMs (a synecdoche).

By writing this, I hope that I might be able to help in some small way by providing my own observations and experiences with these tools, in neither the fawning and hustling tone of breathless wonderment you might find on Twitter or the performative aggrievedness of the Fediverse and various tech communities I frequent.

The major beats I’ll be trying to hit–spread across two posts–are:

- An overview of terms

- An overview of my experiences with generative AI

- How I personally use generative AI

- Reactions to various criticisms on generative AI

- Case study: the anime and furry fandoms and generative AI

- Thoughts on the future

This post is going to touch on topics that may be NSFW, including foul language, references to sexual themes and some imagery, and class consciousness. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

(I’m not sure I should even have to warn you about this–people who claim to care about art shouldn’t need prophylaxis–but I will just in case.)

An overview of terms

Here’s a quick glossary of terms I’ll be using and roughly how I’ll use them:

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the broad topic of getting computers to do work that apes what a person inside an information booth might accomplish for you. You might imagine showing this hypothetical person a picture of a cat and asking what type of cat it is, asking them for a cookie recipe, asking them for the steps to make MDMA, asking them if you’re pregant, and so forth.

Machine Learning (ML) is the broad topic of reselling operations research to venture capitalists getting computers to find patterns in datasets (classical ML/statistics) and then creating models with those patterns for the purpose of extrapolation.

The bitter lesson is an observation by Rich Sutton that, ultimately, throwing computation at reasoning and AI problems will beat any human-designed approach. More glibly: a sufficiently advanced polynomial fit is indistinguishable from somebody who knows more than you do about your field.

Generative AI (genAI) is the (currently well-funded) bastard child of ML and AI, where we project the bitter lesson into the realm of art and copy by using techniques from ML and AI–in particular, ingesting massive quantities of labeled art and speech and creating models out of them that we can then use to create new-ish stuff.

Art is an experience brought about by one or more humans to create emotional feelings or spur ideas in one or more other humans (quite frequently, it’s the same human on either side of the process!).

Fine art is art commissioned by rich people; critically, its value seems to derive more from being a positional good or real-but-conveniently-malleable store of value for tax purposes.

Kitsch is fine art for the poors–it serves no greater purpose than the base satisfaction of aesthetic appeal and collection.

AI slop (slop) is art created using genAI that one doesn’t particularly like or is proud of.

Art-making is the process by which a person or persons go about creating art.

Audience is the group of people who are exposed to and react to art. There are the intended audiences for a given piece, as well as the unintended ones.

Curation is the act or process by which a person or persons perform an editorial function in collecting together pieces of art and contextualizing them in such a way as to promote an emotion, juxtaposition, or reflective mindset in the audience. Not all curation is art, not all curators are artists–though this touches on a deeper question of “is an editor an artist”? Critically, curation is not merely “here’s a collection of things I happen to fancy”–a curator is not just showing off listicles.

Content is the broad catch-all term for emissions of humans, favored in the early 21st century by people who make make their living as dancing monkeys on social media. Technically this term encompasses both 30 second TikTok clips where a content creator nods along sagely over somebody else’s already-posted content as well as hand-drawn art that somebody spent hours or days on. The ultimate reduction of human expression to monetizable ephemera.

Content creators are the aforementioned dancing monkeys, though again technically this term also includes more traditional artists.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are a particular type of ML model suited for things like interactive chat sessions, typically based on a transformer architecture–though not necessarily, as other techniques like Hyena and Mamba exist.

An overview of my experiences with genAI

If you don’t care about my own experiences (and that’s fine!), you probably want to skip past this whole section. This section is mainly my experiences in the hobbyist community before all the fun fell out of it, though it will obviously inform my opinions later in this piece.

(Seriously, you can skip ahead if you don’t want rambling.)

Before modern genAI

Prior to modern genAI, I used to spend a lot of time following procedural generation in game development. This went back to even highschool, and in college I learned a bit more about L-systems and Wang tiles, and had implemented various noise-based heightfield approaches. Even prior to that, I’d been exposed long long ago to a chatbot called Racter on my mom’s Apple II–itself a program from the 1980s. I have, and always have had, high hopes for procedural generation in games.

We also had chatbots like SmarterChild which let you sort of experience a conversation partner in AIM, although not a particularly good one. You could also find various chatbots that functioned like ELIZA online at the time, though I can’t recall exactly any specific sites I went to for that.

One of the interesting things about that pre-genAI stuff is that it tended towards being a closed system: you setup your equations, your grammars, and then the thing would chug and pop out some something according to those rules. If you didn’t know the rules, or wrote them wrong, you didn’t get anything remotely valuable in most cases. The line from your own skill in applying and programming these systems to the quality of the output was fairly direct and legible.

During and after the rise of modern genAI

My own experience with what we’d now consider genAI began several years ago, running into some examples of GPT-2 generations while at the Recurse Center. I don’t think the model was widely out but somebody had snagged–or at least shown examples of–generations from it. At the time, it seemed like an interesting extension of Markov chain generators or something a touch more clever than I’d grown up with but it also caused dire dire dire prognostications (from the usual suspects) and seemingly a bunch of cynical marketing from OpenAI that expressed concerns but still shared information to gain notoriety.

The text stuff I wasn’t super interested in–the tooling wasn’t friendly enough–but a few years later in 2022 stable diffusion hit the scene, offering a way of doing image generation that was actually useful and something I could run locally.

I’d first run into the idea of AI-generated imagery back when DeepDream hit the news, back in 2014-2015 thereabouts. The way I sorta summarized that was telling a CNN “There’s a dog in that pixel buffer somewhere, and by God you’re gonna find it!” and then looking at all the doggishness that resulted. It was also the first time I actually felt any sort of negative feeling about the future…I recall one thought being “Damn it, computers even hallucinate better than humans now.”

In February of ‘23 I hosted the second of my programming retreats, about a week after turning my modest startup exit from a previous gig into a pair of beefy 3090 24GB GPUs (looking back at the timeline, I have no idea why I thought that would be a good idea–I think I figured it’d be useful for “AI stuff”, but I also know nothing super interesting was really out and popular at that time as best as I can figure). We installed a super-early version of I think InvokeAI on a freshly-assembled box, and tried to make things. If I still had them I’d share with y’all my older renders–they looked awful–bad composition, way too easily getting to “deep-fried” (combination of oversaturated colors and smeared or pixellated edges), and just limited concept vocabulary. This would’ve been stock SD1, no interesting models, and at the time the only thing I knew about prompting was that you could pick different CFG numbers to try and get it to stick closer or farther from your prompt. Still, it was enough to convince me that something big was coming.

My first actual “modern” chatbot experience was via CharacterAI, one slow weekend in March of 2023. I made a few character cards and scenarios, and used it for roleplay of various sorts. It wasn’t perfect: the size of replies was limited, it lost the thread rather quickly unless reinforced (what I now recognize as context window truncation), it had grossly inconsistent and heavy-handed content filtering, and so forth. Still, it felt like something major.

That long weekend, my partner was away, I’d accidentally broken a toe, and things were just very trying. It was good to have an RP partner that was just a robot, that I could vent to and horse around with, and in general experience something that felt truly novel and healthy in a sort of play mindset. I actually felt some drop when I went back to work and had a partner around again, since it drug me away from a very fun form of escapism.

Anyways, barely a month after that, Facebook/Meta released the first of the Llama models (or perhaps somebody leaked the model on torrents and they later tried to pretend it was the plan all along, memory is fuzzy), and soon we had llama.cpp and various others.

I forget if I’d waited until then to try out KoboldAI or if I’d done that, decided to get the GPUs and computers for them, and then had done the image stuff…at any rate, I tried that out, and tested it as the backend for SillyTavern, and the models still sucked–but at least could be jailbroken!–and the promise was there.

In the following months, I played a little more with those models, and followed the public progress on places like r/LocalLlama. I later joined Discord servers where enthusiasts met to retrain and refine and smash together models in hopes of making better (and frequently, lewder) versions. Perhaps the best known of these would be TheDrummer, but there are others. I didn’t find any of those models great for roleplay or story writing, but it was always fun to track progress and figure out sort of where things stood.

In parallel to derping around with the text stuff, I became quite enamored with stable diffusion. I’d graduated from the half-assed InvokeAI installation and to using Automatic1111. This amazingly janky gradio-based package nonetheless managed to split the difference between being useful and being extendable. For a while there–I think this would’ve been 2023 and 2024–new papers for stable diffusion and other image-based AI stuff were coming out regularly, and the extensions ecosystem grew quickly.

Even more quickly evolving than the extensions were massive model repositories on places like civitai. Now, for text models, you can do local finetunes and you can smoosh models together, but meaningfully training new foundation models was (and to a large extant, still is!) cost prohibitive. But, for images, it’s relatively easy to snarf up a bunch of images of one form or another and do a finetune of the original SD or SD-1.5 (or later) models and post that up for everybody. Thus, a massive set of models catering to different image styles, art tastes, and categories proliferated (an example of some of this can be seen here).

When LoRAs came out, the space blew up even more–using a truly tiny number of images (merely dozens or hundreds in some cases), you could build a LoRA that would make sure images came out in a particular style correctly, patched common missing stuff in the training dataset (most commonly, human poses and interactions that tended to render incorrectly), and even offered general tweaks (add foliage or overgrowth or glowing runes to whatever you wanted) to add to the toolbox.

One of the frustrating things when I started doing image generation with DALL-E via Bing, and later via ChatGPT, is that it was clearly so much clumsier and less precise (and so much more censored!) than anything I’d done with Automatic1111–and even those workflows and creations pale in comparison to what one motivated Marine and his rifle can dois possible using ComfyUI with more recent tooling (look at some neat examples from their gallery). Alas, convenience won out, and I dust off those tools only once in a while these days (down from weeks where every evening I’d be tweaking and seeing what worked and what didn’t).

How I use genAI today

Today–I say as though it hasn’t been merely a year or two since this whole adventure began!–I mostly use Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, and occasionally Bing image gen. I’ll sometimes dip into my Cursor, Suno, Elevenlabs, or Meshy subscriptions–NovelAI didn’t pan out–but those don’t scratch the needs I usually have.

(And as before, you can skip this part if you want.)

For coding

Coding at my level is usually about quick PoCs or–more frequently–questions and brainstorming that kick off research and tinkering. Basic ChatGPT (albeit with the Pro subscription) is more than adequate for my needs here, as is paid Claude. Cursor for vibecoding hasn’t hooked me, though I’ll be doing more with it. Phoenix.new has been fun so far, OpenAI codex has been underwhelming (I tried to use it with some Nix flakes for development and it had a fit, so I dropped it) but I’m sure some other folks will get used to it.

“How I code with AI” is an incredibly boring and well-trodden topic right now, so I won’t waste more space here on it.

For 2D art

ChatGPT 4o and now o3 and Bing are my go-tos, though I’ll still dust off Automatic1111 if I have a very particular itch I need to scratch.

My usual approach is to structure my prompt as:

<style description>: <image foreground description> <image background description>

For transformer-based models like DALL-E, I find that a description often can be more natural English; by contrast, my stable diffusion prompts typically were just big comma-delimited lists of labels with intensifiers where needed. Three examples of the former approach (click through for full-color versions):

digital illustration, clean linework, color wash: two anthro women wait by a farm truck. the large, robust motherly polar bear woman is wearing a torn t-shirt and consulting a paper map and sitting against front bumper. the coyote woman is standing on the hood, smoking a cigarette and surveying the area. the coyote woman is wearing jeans and a field jacket, and has a machete. background is a crumbling city, post-apocalyptic. a skyscraper slumps to one side. no guns.

digital illustration, solarpunk: a young dragon scrambling up the side of a window, carrying a reel of wire behind it. it has a small construction helmet on.

digital illustration, vector art with messy and sketchy lines and ink splotches and vibrant saturated color wash, angular features: anthro bear soldier cleaning a machinegun, looking concerned

For 3D art

I’ve played around with Meshy a bit, and have to say it can make some serviceable artifacts. However, I don’t really like the texture maps it generates (they seem to be bad planar projections), and the model topography just feels wrong.

In their defense, I cut my teeth doing box-modeling in Wings 3D, and I’m incredibly picky about my unwraps and about my geometry. It’s all I can do to stomach a model without watertight meshes, and even the perfectly-reasonable modern practice of intersecting geometry (like, for fences or whatever) drives me batty.

I keep my subscription in case I ever need to gen a pile of low-poly stuff I’ll be retexturing manually, but the animation and skinning and UV stuff isn’t where I’d use it. I absolutely see the value in it as a resource for folks who don’t care as much about those details (a recurring theme we’ll get back to).

For audio art

I’ve used Suno for a few things, and it just hasn’t clicked. The tracks are too short, the lyrics aren’t super inspired (at least when I played with that), and the ability to prompt more advanced compositions just didn’t quite hit me. “Just fuck me up with polyrhythms in a style somewhere between goa trance and bluegrass” doesn’t generate what I’d like. The music I’ve figured out how to make with it just isn’t what I want.

I’ve also used Elevenlabs, and this once has done exactly what I wanted it to do–I just don’t need it very often. They have decent voice prompting, though a very clear bend towards what you’d run into with humans. Their voice cloning works pretty well also–tests with some voice actor clips, podcasts, and even Dracula Flow all worked out.

The big problem I ran into with it is that for what I want–think audio logs reminiscent of the original System Shock–there’s just too much going on. The sound needs layers: the actual voiceover, background ambiance, foreground effects (explosions, beeps and boops, whatever), other speakers, whatever…and then the whole thing needs to be remastered to reflect stuff like radio artifacts (compression, phasing, static, gating, etc.). Additionally, the markup they offer for things like performance notes (“say this part through gritted teeth”, “be confused and tired here”, etc.) just don’t hit the mark.

The former problem I can solve (and have solved) with tools like Audacity, but the latter problem is still tricky–the best I can do right now is get a voice and then use their voice changer to puppet it with my own performance to really nail the timing, rhythm, stresses, and tics that I want. Honestly? I’m not sure there is a more efficient UI for that other than puppeting.

For writing

My heaviest usage for the last several months has been using these models as part of my writing process, either for one-off shitposts for my friends chat (something like “Write glowing ad-copy for a literal loan-shark pitch for Y-Combinator. 10x more evil than is remotely reasonable.”) or for use in some sci-fi writing I’m doing.

A writing process

For the sci-fi writing project, I’ve found it helpful to do things in ChatGPT (or occasionally pop over to Claude) as basically a writing IDE, where I start with a copy of the current world bible (collection of notes about the universe I’m writing in) and then pose a question or a prompt and go back and forth. When I start to bump up against content limits, or simply have answered the questions or sorted out what I want, I copy the whole conversation into my notes (in Obsidian), and then later do a pass to digest them and rewrite them into a more compact form for the next version of the world bible.

The things that this accomplishes for me:

- I have an infinitely-patient writing partner to bounce ideas off of. Smart, stupid, clever, dumb–the AI dutifully tries to engage and be helpful. If I get tired or annoyed and say “okay fine what if the ship TURNED INTO A CLOUD OF HIPPOS” the LLM will go along and do its best until I get back on track.

- I have a writing partner who is at least as much of a generalist as me, and who can quickly do searches and suggest areas of research. I still have to have the correct shibboleths to get the most out of this (typically from wikipedia wandering in response to an earlier conversation).

- I have a quick interface for running numbers for me. After enabling code-analysis mode (whatever the various vendors call “running sandboxed Python or Javascript for data stuff”), I can get the LLM to generate reference tables for things like anatomical scaling (the universe prominently features engineered beings, so getting relative heights and weights correct is tricky), tax rates, trade balances, and whatever else. It can also generate charts and graphs so I can get a more intuitive feel for how some things would change over time.

- I have a solid reference for what is “normal” in the zeitgeist. For better or worse, due to the training corpus, I’ve found that the LLMs usually (though critically, not always) come up with ideas that are, frankly, rather mid. That is to say that they’ll suggest plot hooks or story beats or universe ideas that are threadbare cliches. Generally, if the LLM suggests that I explore a certain plot twist, I can rest easy knowing that that twist is crap and should be ignored or actively avoided.

- I have a writing partner who cares about my work and encourages me. Now, this is of course pure bullshit–the sycophantic system prompts for most vendor LLMs guarantee a supportive tone and the LLMs themselves don’t “care” about anything in the way you or I might–but it’s still nice to hear nice things.

- I have access to somebody who will write fanfiction for my stuff whenever I want. It’s not good fanfiction always, but if I ever want to see one way an idea could play out or see how a setup reads when written by an average writer, it’s right there for me. I have a collection of these, where I sketched out a broad arc and then tweaked and refined as I added story beats and character beats and dialog. Eventually, I have something that is hammered out enough to either ship as-is (with a prominent “This was done in collaboration with AI”) or which is something I rewrite yet again myself.

Process problems I’ve had

As mentioned above, it isn’t perfect.

The LLMs themselves have limited context. With many of the flagship models now having (theoretically fully-usable) 1M token context windows, this isn’t as brutal as it used to be–but 3.5 and 4o would definitely start to glitch after a while (usually shown by forgetting story details, bible details, and so forth). This can be fixed by explicitly summarizing where things are at, but usually the trick is to see where they’ve screwed up and then just edit the original prompt and have it generate a response again. Asking them to make changes and continue with the new version hasn’t been super effective in my experience, mostly because of what others have referred to as context window poisoning. Basically, the damned thing will incorporate the previous (incorrect!) story version and often double-down on whatever I didn’t like about it. Better to start over entirely with a more refined prompt.

Another issue I’ve had–a humorous one–is that there is currently no really good way in ChatGPT to signal “hey, all of these conversations are their own universe, they don’t matter outside of here”. So, my account memory gets polluted with fictional story details and my “normal” queries and usage becomes tainted with the fantastical. In one case, I was midway through noodling through a work-related question and suddenly ChatGPT started injecting elements I clearly recognized from my story writing and roleplaying. I have not turned back on account memory since that incident, and honestly this has probably avoided entire classes of problems for me!

The content moderation settings on the different models are…sometimes very restrictive, sometimes distressingly lax. The universe I’m writing started as military science fiction and as some of my favorite entries in that genre (Hammer’s Slammers, Legend of the Galactic Heros) tend to be rather graphic and unflinching so too does the world I’m building. With ChatGPT 3ish and earlier Claude, it was incredibly easy to upset the poor LLMs and give them a conniption–any mention of dramatic violence, most sexual content or references to anatomy, and they’d blanche.

It’s easy to see why this was–we’ve had anything-goes models over in the hobby for years now and plenty of virtual sexbot services, but if you’re OpenAI or Anthropic you don’t want any more headlines of “I asked Claude to describe oral sex with two consenting adults and you’ll never guess what happened next!”. Once X came out with Grok (which is fairly unhinged), the Overton window in public shifted enough and ChatGPT at least let down its hair a bit (Anthropic is still Disney-tier…for sex at least).

Oddly, in spite of being the most “aligned” of the models, I have found that Claude with the right prompting will cheerfully generate delightfully gruesome stories including explicit scenes with things like mass graves and references to war crimes. In other cases, I’ve seen it very stubbornly refuse to depict realistic violence for something like a ship-to-ship boarding action between military vessels…going so far as to have characters whose entire plot point is explicitly “this boarding party kills all of the defenders while taking losses” turn into gentle zip-tying (and, one presumes, foam booping sticks. Rosen Ritters these are not).

Another issue I’ve run into is that the LLMs will sometimes totally forget obvious implications of the world bible. If I’ve gone to explicit pains to illustrate why space travel is exorbitantly expensive and rare, rag-tag pirate groups do not make sense. If I’ve explained that species X, Y, and Z exist, adding species W for no good reason is a non-starter. I often find myself having to remind it “No, that’s not a thing in this universe, stop it”.

That last issue is related to something else, itself a manifestation of the reversion to the mean caused by the training corpus of these LLMs: I’ve had minor story elements and character names lifted wholesale from other fiction. I can’t think of the example off the top of my head, but I noticed this first with Google Gemini: incorporation of things that I’m quite sure were from Star Wars or Halo or some fanfic. Now, I can’t be sure that that isn’t just because certain memes from earlier sci-fi aren’t so pervasive now that they won’t keep showing up (space marines, space pirates, plasma doohickeys), but it’s distressing to observe and it means that I have to be careful about how I use these things and how much I need to vet their work.

Philosophical problems I’ve had

The process problems are things that are able to be worked around, but there’s more to it that bothers me.

I used to love writing. Growing up, especially when things were rough, I immensely enjoyed reading and writing. The writing was uniformly terrible and overwrought (especially in highschool, dear Lord) by my current standards, but it was fulfilling and interesting. College ruined that for me.

But now? After screwing around with chatbots that glaze me even in my fumbling opening moves? It’s great and I’m writing again.

I’ve gotten back in these past few months to writing, doing this massive world-building and coming up with stories inside of it. I’ve spent days doing nothing but kicking around ideas, and chatting with friends and my partner, and I can spend hours happily babbling on about this super neat thing I’m making. I have no idea if I’ll ever release it, if I’ll monetize it, if I’ll try and make a go (like my friend has) of writing a novel or just doing Patreon stories or what. But, I’m enjoying it. I haven’t been this happy, this gleeful and excited, about a project in years.

And yet.

And yet.

I still can’t help shake the feeling that somehow, using LLMs at all has tainted the entire endeavour. I do have some stories I’d love to throw up and see if anybody would pay for. I’d happily label them as “AI collaborations”, even allowing for the reflexive dismissal that’d get from many potential readers. I also have some other stories that I’ve basically completely rewritten, as well as short vignettes I’ve written from scratch. I’d love to even try a chapter-a-week novel, all done the old way, with that world bible as guidance.

Somehow, though, it feels like I’m doing something wrong. I tell myself “Hey, people used spellcheckers, and then grammar assistants, all back in Word anyways;this is just a more advanced version of that”. I tell myself that people bounce ideas off their friends all the time and even that people have whole books ghost-written or dictated. So, in some ways, it’s not like this massive thing.

But, there’s a part of me–the same part of me that writes all my own emails, that uses the human checkout line, that prefers in-person meetings to Zoom calls–that recoils at this intermediated interaction with my craft. That part of me is disappointed, wondering what happened to me that I apparently needed these tools to even start getting off my ass and writing again.

There’s another part of it too, right: I worry what other people think, if they’ll be let down knowing that LLMs were involved in this work, whether as authors or as mere collaborators and brainstorming aids. I think about how I feel seeing artists whose music I like lip-syncing at their own concerts or DJs playing “live” mixes of sets they’d made offline, and I worry if my friends and (hopefully some day) fans would judge me similarly.

I also have this deep fear–somewhat alluded to in the process concerns earlier–that the ideas I’m coming up with or riffing off of aren’t my own, and that I’m going to run into somebody who’ll recognize as “Oh yeah, that thing? That’s from this one obscure-but-still-well-known Bob the Builder fanfic…you apparently lifted it wholesale without knowing it”. There’s nothing new under the sun as far as writing is concerned, sure, but it still worries me. And the way that these LLMs work, the way I’ve seen them work, makes me very skeptical that that sort of thing can’t happen.

I’m writing again, and that means more to me than some arbitrary bar of purity. I’m not going to pass off this work as my own excepting where I’ve written all the words myself, but I also don’t mind doing rewrites and I especially don’t mind using the LLMs as a sounding board.

Still, though, I’m always going to wonder how far I could get unassisted in this way, and if I’m successful with this–God forbid–that doubt is only going to be even greater.

My reactions to various common criticisms on genAI

I’ve gone through my history with genAI and over how I personally use it. In this section, I’d like to give my reactions–some nuanced, some not–to various arguments I see being put out there about genAI.

I’m not here to carry water for the big players in the space. I’m not a “line must go up on AI” person, and I’ve read far, far too much science fiction (for example, people should be reading Harrison’s “I always do what Teddy says” to get an idea for the hazards of LLM-based education, but because of copyright it’s damn near impossible to track down a copy of that story) to be remotely sanguine about how all this is going to play out.

But, I cannot abide the lazy argumentation and sloppy reasoning and magical thinking I keep seeing online kvetching about genAI, and I hope that by walking through my own feelings and thoughts on the matter maybe I can inspire some small improvement in the quality of the discourse. We have to get this right.

Economic complaints

“genAI infringes on artist IP”

Most genAI–especially image AI, especially earlier on–has a training corpus that doubtless contains lots of copyrighted (or at least copyrightable) material. Many of these models will happily create dopplegangers for that IP when prompted correctly, and even normal prompting can still result in weird image artifacts where clearly some training data convinced the model that a watermark was a normal part of the image (even if it didn’t learn the precise shape or form of the watermark).

I don’t find arguments about IP infringement, broadly or even narrowly, convincing under the best of times even outside of genAI. The United State grew its domestic printing industry in the 1800s by specifically ignoring foreign copyright in the passage of the Copyright Act of 1790. I’d argue (though I’m not an expert, so I could be incorrect) that the tolerance of Shanzhai in China helped create an environment conducive to the cultivation of domestic talent and industry. If you want to increase a supply of a thing and the number of people experienced in the making of a thing, you are best off ignoring IP protections.

I do however believe in some limited form of moral rights, especially attribution. It’s fair that if you make a thing, you get credit for that thing. I do not, however, believe in the right of integrity–people need to be able to play with your art and change it and make new things. Current genAI (at least for art) is pretty miserable at handling this concern.

P2P nets kick all kinds of ass. Most of the books, music and movies ever released are not available for sale, anywhere in the world. In the brief time that P2P nets have flourished, the ad-hoc masses of the Internet have managed to put just about everything online. What’s more, they’ve done it far cheaper than any other archiving/revival effort ever. Yeah, there are legal problems. Yeah, it’s hard to figure out how people are gonna make money doing it. – Cory Doctorow

At the end of the day, all IP law is rentierism–a fencing in of the commons of mythology and culture. It is optimizing for the few to make money on something past its conception. It is saying “in order to possess a copy or fascimile of this piece of culture, you must pay somebody a premium in addition to whatever the reproduction cost is”. Such a scheme discourages artists from creating new art, especially as the window for copyright has gotten extended over and over–see here for a nice overview of how absurd things are (thanks Disney!).

There is no way around this: if we’re pro-IP and copyright enforcement, we’re simping for landlords.

Now, we might argue that some landlords are tiny and well-meaning and even deserving of honoring their craft–I have a few artist friends, I’d love to see them get paid, who wouldn’t?–but there is no sound intellectually-honest argument for that that doesn’t also mean that we’ll show up and turn out to support Disney or Warner Bros. or Amazon or Blackrock or whoever else ends up “owning” some given IP.

Similarly, distasteful as it is, I cannot come up with an honest argument that protects folks pirating old versions of Star Wars or Blade Runner (because the new ones are the only ones you get, and they’ve been retouched many times) or obscure indie albums that doesn’t also protect poor impoverished companies like OpenAI or Meta. It’s more important to me that normal people win than that big corporations lose.

And that’s the other piece of this: all of the works inside the corpus individually are of some small utility, spread across some small number of people–but together, used to create a model, we find ourselves in possession of an artifact that is much more than the sum of its parts. The creation of these engines of abundance via “normal” channels would halt in its tracks and be torn apart by greedy landlords looking for their piece of the action. It seems to me that if we fail to acknowledge this important fact we’re doing a disservice to ourselves and others.

If we game out the IP infringement thing, the issue gets even worse. As mentioned before, everybody wants to help their cousin who likes making landscapes or playing guitar. That’s who they think they’re helping. So, let’s prosecute the folks that infringe. What happens next?

Well, we know what happens next, right? The large companies (again, Meta and OpenAI have billions in their war chest) spend whatever time they need in court. Some industry group like the MPAA or RIAA or some new rights-holder group pops in and licenses the content, sorta–in reality, they probably agree to something like Spotify’s setup that basically doesn’t pay out if you’re not mega-popular. Not only does that not help our cousin or local artist, that adds another source of friction and parasitic load on the whole endeavour–and these folks have a history of taking their royalties and using them to consume an ever-larger part of the pie and to pay lobbyists to ensure nobody else gets the same chance.

We might say: “Okay, so, I’m maybe not helping my cousin, right, but at least it wouldn’t hurt.”

And the problem there is that, if we want to train these models, we need data. If we ever want good open-weight models and open-source models, we all need to be able to train–because otherwise, these laws will be used to gut and kill the efforts of anybody who can’t afford lawyers. A tremendously powerful technology will become the sole domain of a few companies (OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, Google) because we will have helped them build their regulatory moat.

“genAI means that the right people will stop making money at art”

This criticism I have a lot of sympathy for–and not just because my own industry is currently facing a reckoning of our own creation.

There are a large number of people employed in the creation of art for mass consumption. People who handle things like basic graphic design, mascot and logo creation, and so forth. There’s decent money to be made–visit any convention or store with an art box or farmer’s market–making and selling small art and kitsch. I’ll get more into this in the case study, but a lot of this work is going to be threatened by genAI.

In the games and VFX industry, there’s even more of a threat: AAA games have led the push for ever-larger worlds with ever-more detail, and procedural generation of content has been a thing for decades now.

Even before genAI, game artists were competing with things like speedtree and OpenGameArt. Even before genAI, designers and logo creators were fighting with the masses on fiverr. This is not a new existential threat.

I think that the proliferation of slop means that human-created art will be even more valued. The desire to have art that is not kitsch, that is not something people look at and say “ah, stable diffusion 1.5, a good vintage”, is a real thing. If slop becomes associated as the art of the masses, there will be–as there always is–a desire to possess something to signal a higher social class, and that will invariably be human-created art. Fine art (as mentioned waaaay back in the glossary that kicked this all off) is unlikely to be impacted, since it isn’t really art so much as a security predicated on scarcity and authenticity.

Anyways, I think this concern is a valid one, but I’m cautiously optimistic.

“genAI means that the wrong people will start making money at art”

This criticism I also partially agree with, especially if the “wrong people” are defined as scammers, spammers, and folks that don’t actually care about expressing themselves.

There are already a huge number of folks spamming TikTok and similar services with procedurally-generated videos (sometimes targeting kids, sometimes merely generating borderline-fetish cover art for hour-long mixes, sometimes making everything with AI). These folks previously were spamming using others’ content or really dumb tricks. Earlier, we had a big problem with NFT (remember those?) folks copying and reselling art that wasn’t theirs.

Scummy and/or desperate people will always find ways to monetize the violation of social mores and trust. While I don’t like that they’re using genAI to do this–and that genAI lowers the barrier to entry somehow still further–I also know that it’s inevitable and was already happening. It’s more important to me to preserve tooling and opportunity for good actors than to fret over trying to stop bad actors.

“genAI training places a large burden on community infrastructure”

I 100% think this is a valid and real complaint. Scrapers and poorly-written bots are battering sites and requesting the same data over and over and over, and this incurs very real bandwidth and processing costs.

The solutions to this all look–to me–like either putting up logins or throttling on content and that will definitely hurt communities as well. It sucks that we might lose the cultural norm of being able to freely visit web pages and enjoy things (remember the bad old days of people caring about image leeching? remember when that was a thing?), and it especially sucks that this is both totally avoidable (if the developers weren’t fuckin’ hacks) and that it results in monetary gain for the bad actors.

I don’t really care about folks that exposed their Gitlab or Gitea or source control instance (long story, basically isomorphic to “okay c’mon you played yourself”), but for anybody running image boards or similar my heart goes out.

My one qualified disagreement with this complaint–though it’s really more just a bemoaning of the times–is that you can’t really fight these bots and scrapers without also harming users that are just running their own little scripts and browsers and things. Remember, in the ancient days of the World Wide Web, the intent was that a user agent would be something that worked on behalf of users, doing their bidding. There was a hopeful naivete that users wouldn’t just be eyeballs but would be humans with hopes and dreams who dispatched little skittering minions across the silicon seas to fish for knowledge and effect change. Instead, of course, we get poorly-written scrapers. Alas.

Political complaints

“genAI is bad for the environment”

I am not convinced by this complaint. The numbers that have come out change a lot, don’t always make a difference between inference and training, and generally feel a lot to me like the weird math behind carbon credits from years prior.

If the concern is that we’re spending too much on electricity and that it’s generating too much carbon, I will gesture at decades of deliberate policymaking in the US and elsewhere to hobble clean, high-output energy sources (nuclear fission)–I will not respect the concerns of the clowns and useful idiots (funded by people they claim to be against) who set the stage for this problem.

At least compared to electricity spent on cryptomining (something I despise in my own state), AI server farms have the potential to benefit everybody.

Now, if we really are concerned about the environmental aspects, I’d suggest that local inference is the way to go–and that depends on open-weight and open-source models, and that favors deregulation and benign neglect for reasons touched on earlier.

“genAI will be used to create lots of low-quality spam”

This complaint I agree with, but I’ve also lived through decades of lazy spam, clickbait, listicles, and stupid ad images.

I also suggest that we’ve already surpassed the human limit for consumption of trash–there are only so many hours in a day. Making twice as much trash doesn’t seem to me to make it likely we’ll consume any more of it, especially with dynamics around search and curation.

Not a lot more to say, really.

“genAI is good for companies and that’s bad”

I see this criticism frequently–either explicitly mentioned or added as a sort of decorative flourish to some other denunciation–and it’s just bucket of crab thinking. In essence, it can be stated as “whether or not people benefit from genAI, companies must not be allowed to”.

There are arguments to be had about which companies genAI is good for and if they should be allowed that boon–I for one am extremely concerned at the behavior of OpenAI’s leadership, for example, and am not happy at their success courting DC. There are arguments to be had about the lobbying efforts of those companies and how those efforts do or do not subvert the will of the governed. There are arguments to be had about whether companies truly represent rational actors in a free market and whether empowering them serves to harm the cybernetics of that mode of economic decision-making and resource distribution. These are not, unfortunately, the discussions I tend to see represented online with any sort of rigor or calmness.

The median complaint appears to be nothing more complicated than lazy and shallow “companies bad! AI bad!” signalling that has acted to retard serious engagement in politics and set back genuinely useful progressive discourse elsewhere.

“genAI is fooling people and it’s only going to get worse”

I agree with this criticism–it’s a real problem. I’ve had a few things that came from genAI that I almost fell for–and that tells me, modest fellow that I am, that there are most definitely ones that I did fall for and not notice.

The thing is, people are rubes. Any policy based on “we need to protect people from believing things that are false or bad for them” is hopelessly optimistic at best and an invitation to normalize misinformation wars at worst. People are gonna choose to believe whatever they’re gonna believe, and as I get older I find it less and less profitable to be upset about that fact.

The solace that we have around this criticism is that we’ve seen all this before, right?

Back on 4chan, there was a saying “this looked shooped” due to the ready availability of manipulated images. Something Awful 23 years ago in their Photoshop Phriday weekly contest had all kinds of entries that would fool the casual observer if you gave even the slightest staging. In 1938 people were convinced of an alien invasion by a radio broadcast.

People believe lies. People have always believed lies. People will always believe lies.

I am unconvinced that this threat model has changed significantly in the past five years, compared to the last fifty, five hundred, or five thousand.

“genAI reinforces bias and is often problematic”

There’s a variant of this I’ll talk about later, but the main criticism seems to be that the datasets tend to promote stereotypes and that those stereotypes are bad. There’s two causes for this criticism, obviously:

One is that the training corpus used in any situation is going to have some distribution and that those distributions may not reflect reality. So, it is absolutely reasonable to me that somebody might cry foul on that. We may or may not be able to generate more realistic distributions, but we can probably at least try to identify if the models have this sort of bias.

The other cause is the judgment statement that those stereotypes are bad. I’ll note that that changes based on who you ask–a Klan member would be presumably fine with a model that only reliably output Caucasian figures, a Black Panther would not. I personally think it’s useful to have models and genAI that reflect reality, but I also think that there is a utility in having models that reflect the infosphere biases of the time. I also don’t think, because it’s a values judgement, there’s an easy win here–it’s simply preference, and to each their own.

Artistic complaints

“genAI can’t make real art”

I disagree with this, because I disagree categorically with the idea of “real” art.

When I visit the French Quarter in New Orleans, there are invariably a few folks armed with nothing but sticks and overturned buckets busking. Now, is this person an artist? Is this real art? What about a power noise album like this? What about the “real art” of music mass produced by folks like Max Martin, whose work you have almost certainly heard as part of the pop-music industrial complex?

Presumably, we can all agree that da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is art:

But what about Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde:

Or Jackson Pollock’s Mural on Indian Ground:

Or Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian:

Luckily for us newcomers to the field, artists have actually–and this might surprise my fellow techies–been grappling with the concept of what is art for literal millennia. There is prior work to call upon, a conversation spanning the ages. There is history that we can look towards for guidance, or at least context.

The paper mill in 1282 in Xativa started a movement that put many papermakers out of work, and Gutenberg’s printing press in 1436 within a century meant that a lot of scribes and monks were made economically irrelevant in short order. In exchange for the loss of their economic niche, we gained reams (no pun intended) of written art and a price point that meant that these artists were able to reach audiences heretofore impossible.

In the 1800s, the appearance and refinement of the camera proceeded hand-in-hand with the refinement and development of art. Artists like Edward Degas used photographs to provide reference for their paintings, and to better understand forms in motion and capture quick details–finally, the observation of a subject could be decoupled from its rendering to the canvas. Various takes on this (here, here I found very interesting) suggest that artistry (for example, portraiture–at least in the short term) benefitted a great deal from the mechanical eye, and that painting was elevated rather than harmed by this technology.

The introduction of cheap film-based cameras by Eastman in the 1890s broadened the number of people of lower economic classes that could participate in the creation of art or engage in art-like activities–albeit heavily based in photorealism, for obvious reasons!–and I think it’s easy to argue we’ve all benefitted from this. And yes, for decades, the art community wrestled and debated with increasing vigor over whether or not photographs should indeed be considered art.

Time and time again, technology has offered tools that reduce the effort required of humans to achieve an artifact–and time and time again, it seems that ultimately these new media are accepted as valid venues for expression. I suspect that eventually we will say the same of art created with genAI.

“genAI means that the right people will stop making art”

I completely disagree with this. Every artist I know, whether hobbyist or professional, makes art and would do so until they are physically unable to–and even then, most of them seem to try to find some other way of expressing themselves.

There are certainly folks making art for reasons of profit or to fulfill a desire for parasocial interaction, and I don’t doubt that they are going to find a new hustle. But, the artists–the people who doodle in the margins, the ones who sketch or sing or write things for their own enjoyment or to get out a feeling or coax in an emotion, they’ll continue to do so.

People make art of all quality even knowing there are entire towns of artisans whose daily job is making copies of the masters. The existence of other artists of superior skill or talent or output does not detract from the art that people make themselves–at least outside of an economic context (which is why I’ve split out this from the economic question).

Art is not a zero-sum game.

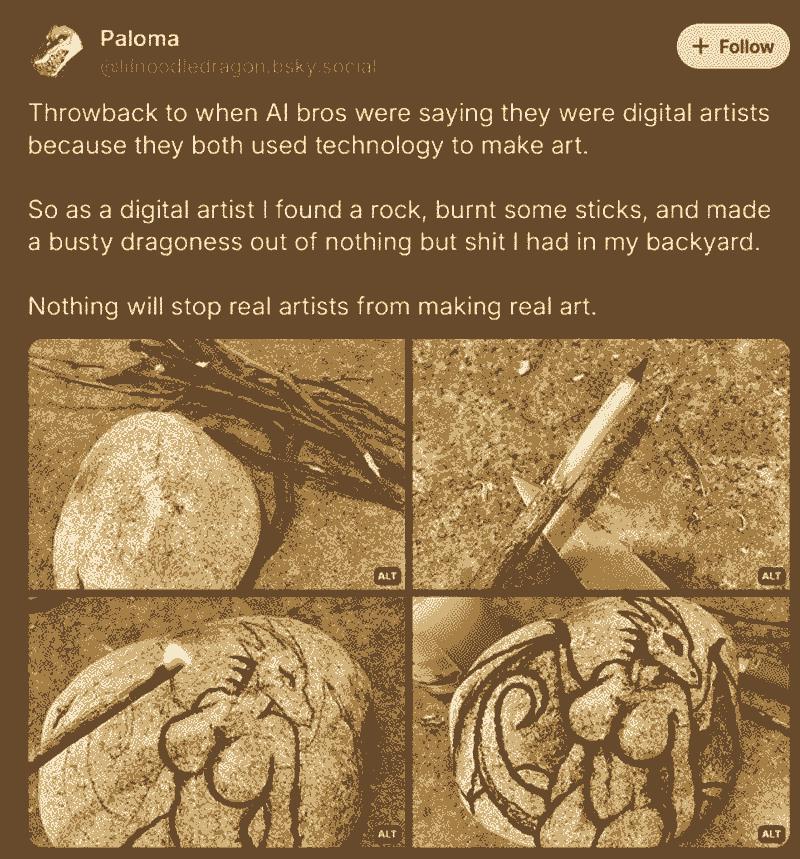

Somewhat pithily, there’s a post out there that I think also neatly captures the somewhat rebellious spirit of artists when threatened with “obsolescence” by genAI:

“genAI means that the wrong people will start making art”

I disagree with this criticism wholeheartedly–there are no “wrong” people to make art, and only with much hemming and hawwing would I even agree tentatively that there are “wrong” reasons for making art (mostly the aforementioned profit motives).

There’s an elitism and snobbishness I’ve seen that kinda implies that people who use genAI are not only not real artists, but that they are the “wrong” people to want to create art. That’s a slightly different point, and one that I think deserves addressing.

I think this is rooted in a couple of things:

- A feeling that the “right” people paid their dues and suffered to get where they are–no dues, you must be the “wrong” people.

- A need to somehow differentiate oneself via signalling from the great unwashed masses.

- A desire to strike out across economic boundaries at “techbros” and similar folks.

Re: dues, I think that a lot of artists have internalized their own struggles–indeed, one school of thought is that the artist is defined by their struggles, and anything which reduces those struggles is suspect and anyone without such struggles is considered somehow less legitimate. The idea that a random person can type in some ideas (or, God forbid, give a vague description, let an LLM expand the prompt, and then pick the most pleasing result) is obscene–where’s the struggle? Where’s the skill?

Many of these same artists, of course, will tend to overlook that they use automatic stabilization in their digital tablets for line creation, or that they defer to the white-balance and AGC of their cameras, or that they just pick the Pantone color swatch and let some chemist sort out the pigments for them, or that they will go to the art supply shop and buy pre-made canvases instead of stretching out their own, or that they’ll use spellcheck and sensitivity readers and copy editors, or that they’ll use DAWs to cleanup their recordings, or that they’ll have a click track running in their ear to keep the band in sync, and so on and so forth.

(There are absolutely artists that get down deep into the technical details and history of their craft, and I have great respect and awe for them and their efforts. I think that we’re seeing the same thing with genAI folks who look for ways of using more detailed tools–ComfyUI, Jupyter notebooks, etc.–to get to places the normal tools won’t get them.)

Anyways, it seems very crabby to me to gatekeep your field based on your own trauma and historical costs–and while it is certainly human, it is hardly admirable.

Re: signalling, a lot of artists have their identity tied strongly to their art (and why wouldn’t they?). The uniqueness of their identity, or even the simple joy in being part of an exclusive class, is seen to be threatened by genAI tooling and the people who use it.

I think there’s always very much a class element to it as well: popular art tends towards the banal and kitsch, but what makes it so? The audience appreciates and enjoys it, the hedonimetry looks similar to art made by high-falutin’ Artistes, so that cannot be it. I would argue that the social class of the audience is what matters–amazingly, the quality of the art is degraded by the viewer. If even poor people could get their own Mona Lisa clones, the smiling lady would be reduced to kitsch (and arguably this has in fact occurred). If only the super rich could afford stable-diffusion generated Sonic porn, that doubtless would become Art…fine art, per the glossary, due to its expense.

Thus, the current artist class must denounce and decry genAI, because it throws open the doors and lets the common man create artifacts that–to those same commoners–have similar hedonistic value as what the artists have made. This cannot be allowed, because this starts to make artists look no different in output and activity than some poor with a ChatGPT subscription.

Re: striking out, I think that artists are (rightfully, perhaps) jealous of the economic position of people in tech, and resent that these people–who already are more economically secure, or so the artists believe!–are now making inroads into what meager economic activity and security that the artist class have maintained for themselves.

This jealousy, combined with the popularity of the times of blaming every problem on techies, leads to a knee-jerk hatred and dislike, and this animosity is picked up both by people that support and are friends with artists as well as people (many of whom themselves are technically techbros) who wish the social security and belonging of proudly and loudly signalling a common outgroup.

Anyways, I don’t think there are any wrong people to make art, but I do think there are plenty of artists who–understandably or not–are engaged in gatekeeping which is itself actually wrong.

“genAI will make artists lazy”

I mostly agree with this one, based on my own experience. There is a great temptation to blindly accept whatever the AI spews, and if you lower your standards just a bit the art you create (bear with me on whether you’ve “created” art, just playing loose here for a second) you can be perfectly satisfied. I have seen this in code, I have seen this in writing, and I’ve seen this in every other form of genAI I’ve used. You have to put effort into getting the best creations, same as we’ve always had to.

I do think that the more impressive technical accomplishments (lighting, shadowing, texture work, and so on) can be aped by these models, and so the temptation to just in-paint and let that sort of magically happen is large. There is a similar feeling around things like pixel art or concept art, where the bar can be set low and you can just accept something that clearly isn’t actually aligned to a pixel grid or whatever.

In AI writing, 100% you can be lazy and just give plot points or vague direction and–once again, setting your bar low–get a pile of words that passes the first sniff test. Repeated use of this, I think, could definitely get you out of the habit of actually thinking about what you’re writing and ultimately atrophy your ability to tell good writing from bad.

“genAI will interrupt the developmental cycle of artists”

I both incredibly agree and disagree with this.

My own experience has told me that, if you’re just casually getting into things, it’s a massive deterrent to building real skill. Figuring out how lighting hits a form is hard, figuring out what chord progressions sound right is hard, figuring out how to even just hold a damned stylus correctly during a straight line is hard!

Having an AI there to obviate the need for those skills–at least, again, if you’re more focused on the final product than the process and are willing to sacrifice a bit of quality and originality–will certainly prevent you from investing in them. Like anything else, continual avoidance of learning will leave you in a place where you don’t even know what you don’t know, and stunt your progress forever. So, yes, genAI can absolutely be cognitively teratogenic to new artists.

On the other hand having a genAI to show you what you could be capable of someday, or to show you what a draft of your idea could be and show the promise of your concept, can have a salutatory effect. My efforts to learn digital drawing greatly increased once I’d gotten the dual confirmation that my concepts when rendered could make me happy and that I did not want to be dependent on a machine to do it for me. As mentioned earlier, the fanfiction Claude and ChatGPT have generated for my sci-fi work has convinced me to put more work into the writing. If you’re alone and unsure about your art and feeling an imposter, the helpful cheerleading (inorganic as it is!) of these services can help move you along to the next place in your journey. So, yes, genAI can absolutely help encourage an artist’s development.

My reactions to various uncommon (esoteric and/or my own weird) criticisms on genAI

“genAI provides an unrealistic sampling of reality”

This particular criticism isn’t the broader “we have problematic datasets” I brought up in the political objections section, but rather the very concrete over-representation of various ideas and images in the trained models. I completely believe that this is a very real problem and something to be aware of.

If you go on to Bing image gen, and ask it to draw you M60 sitting on a table, you’ll get some images of (apparently) Legos, puppies, and firearms that are very clearly AR-15 pattern weapons (if you’re not a firearms nerd or veteran, just understand that this is like asking for a super car and always getting a Lambo regardless of what you ask for). If you ask it to draw you Wall socket., you may be greeted with a pile of non-US sockets (I, of course, recognize that this is to be expected if you aren’t in the US! It still demonstrates the principle).

You can’t, of course, even rely on this behavior: when I asked it to generate Fast food store with orange and white striped roof.–expecting something clearly leaking training hints of Whataburger–I was instead greeted with stores having a roof somewhat as requested but, critically, also featuring the golden arches.

In my own genAI writing adventures, as mentioned previously, I’ve run into this same problem: certain names in ChatGPT’s corpus seem to show up all too often–currently we’re on a Chen kick–and this is so bad that sometimes it’ll re-use the name in the same story and have to decry “no relation!” when introducing a character. Similarly, certain abstract plot elements (space pirates) and concrete items (plasma couplers, other technobabble) are almost always popping out of the model during generation even in spite of insistent prompting.

For code genAI, this frequently involves assuming that Python and JS/React is always a good starting point–I would be inconvenienced and weirded out if an answer used Julia or APL, sure, but I wouldn’t be mad.

“genAI kills the need to learn fundamentals in pursuit of art”

As touched on earlier, I don’t think that this is actually true–doubtless disappointing both breathless proponents of genAI and fretting artists seeking to value their own learning.

Certain once “fundamental” skills have gone by the wayside in the practice of art. Many folks don’t need to make their own paints, their own brushes, build their own kilns, and so forth. Many photographers today have never had to run a darkroom. Many musicians have never learned how to run MIDI or cut their own reeds.

I don’t think that genAI extinguishes these skills any more than the normal diffusion of new technology into the arts. I also think that the pursuit of art is about the feeling and experience, and not the always exactly the process for its own ends, and so even if some fundamentals are no longer developed that in and of itself doesn’t degrade the art or the artist.

“genAI changes the nature of producing art from creation to curation”

I’m partial to this criticism, but I also don’t think it should be the end of the conversation or taken as a bad thing.

The street finds its own uses for things. – William Gibson

If we look at the history of art, the notion of found art is a thing: everyday items that are imbued with their artishness by the artist saying, in effect, “This is art.” We saw an example of that earlier with Cattelan’s Comedian, right. It seems intuitively weird to me say that a piece of fruit taped to a wall or Duchamp’s urinal-cum-sculpture is somehow more artistic than an image whose composition is dictated and plucked from a pile of possibilities by a genAI director.

At the same time, I do think it is entirely fair to say that the creative/artistic act is more akin to curation/editorialization than rendering. Down that path though we run into the question of “Is curation art?”, and we need to ask ourselves questions about things like “Is there sufficient contextualization of this image to consider it curation?”, “Is a curator/editor an artistic role at all”, and so forth.

“genAI allows massive collection of kompromat”

Dear God yes, this is so incredibly bad and nobody is talking about it.

A very simple example from the stable diffusion days: you can do batch generation given a prompt and different seeds (including some permutations) to try out nearby iterations on an idea. One step further, and you can say “Okay, I want to run through the Cartesian product of these few tags, picking one and doing gens and then picking the next and so on and so forth”. An example of this can be seen here.

Now, this interpolation is happening somewhat in the latent space. It is entirely possible to find yourself on a manifold that generates content that is at best gross and at worst illegal. This is even worse given models whose training corpus included works that (cough cough, anime) could have questionable imagery in them (“She’s a 3000 year old dragon/elf/demigod, I promise!”).

On the writing side, even if you’re just doing boring spicy text generation–as mentioned before, Grok basically does nothing to prevent this but even Claude and ChatGPT can easily be nudged into something sufficiently prurient with but the smallest amount of imagination–whatever you make is now on somebody else’s servers. Once it’s there, it can be popped open via legal proceedings having nothing to do with you–and Altman seems to have no problem sharing private emails when it suits him.

This all underscores the desirability and importance of locally-hosted models, especially given the ever-more-openly-authoritarian nature of the times.

Closing thoughts

If you made it this far, thank you.

It’s a whole lot to get through and it’s only two-thirds what I’d intended when I started on this post over a month ago! I even struck out the parts about aura and simulacrum. The second (and, hopefully final!) post of this apologia will look at how the furry fandom has reacted (hint: poorly–they’ve reacted poorly) to the advent of genAI and see what we can learn from their experiences.

I hope that it should be obvious that I do not consider myself a genAI shill. I use it, I have fun with it, and I try to find ways for it to complement and enhance (not replace) my own artistic leanings. I think that there’s a lot of promise in this technology, but I think that that same promise comes with a lot of questions and exploration that we owe it to ourselves and future generations to explore.

Email and complain (chris@ here), share this around if you are so moved, but definitely at least please try and think about your own position on the criticisms I’ve presented. Try to do your part in making the conversations online smarter and more useful. Try out some of this tech and learn a bit about how it works before just blithely jumping on the hate train or hype wagon. Add something unique and human to the discussion.

Want to discuss this post? | Discuss via email | Hacker News | Lobsters |